Four-vector

In the theory of relativity, a four-vector is a vector in a four-dimensional real vector space, called Minkowski space. It differs from a vector in that it can be transformed by Lorentz transformations. The usage of the four-vector name tacitly assumes that its components refer to a standard basis. The components transform between these bases as the space and time coordinate differences,  under spatial translations, rotations, and boosts (a change by a constant velocity to another inertial reference frame). The set of all such translations, rotations, and boosts (called Poincaré transformations) forms the Poincaré group. The set of rotations and boosts (Lorentz transformations, described by 4×4 matrices) forms the Lorentz group.

under spatial translations, rotations, and boosts (a change by a constant velocity to another inertial reference frame). The set of all such translations, rotations, and boosts (called Poincaré transformations) forms the Poincaré group. The set of rotations and boosts (Lorentz transformations, described by 4×4 matrices) forms the Lorentz group.

This article considers four-vectors in the context of special relativity. Although the concept of four-vectors also extends to general relativity, some of the results stated in this article require modification in general relativity.

Contents |

Mathematics of four-vectors

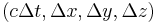

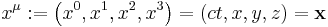

A point in Minkowski space is called an "event" and is described in a standard basis by a set of four coordinates such as

where  = 0, 1, 2, 3, labels the spacetime dimensions and where c is the speed of light. The definition

= 0, 1, 2, 3, labels the spacetime dimensions and where c is the speed of light. The definition  ensures that all the coordinates have the same units (of distance).[1][2][3] These coordinates are the components of the position four-vector for the event. The displacement four-vector is defined to be an "arrow" linking two events:

ensures that all the coordinates have the same units (of distance).[1][2][3] These coordinates are the components of the position four-vector for the event. The displacement four-vector is defined to be an "arrow" linking two events:

(Note that the position vector is the displacement vector when one of the two events is the origin of the coordinate system. Position vectors are relatively trivial; the general theory of four-vectors is concerned with displacement vectors.)

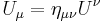

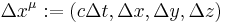

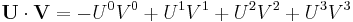

The scalar product of two four-vectors  and

and  is defined (using Einstein notation) as

is defined (using Einstein notation) as

where  is the entry in the

is the entry in the  th row and

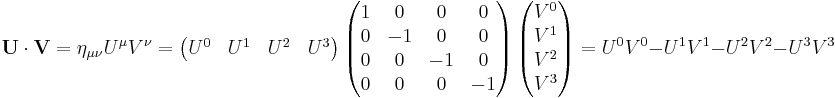

th row and  th column of the Minkowski metric

th column of the Minkowski metric  . Sometimes this inner product is called the Minkowski inner product. It is not a true inner product in the mathematical sense because it is not positive definite. (Note: some authors define

. Sometimes this inner product is called the Minkowski inner product. It is not a true inner product in the mathematical sense because it is not positive definite. (Note: some authors define  with the opposite sign:

with the opposite sign:

in which case

Either convention will work, since the primary significance of the Minkowski inner product is that for any two four-vectors, its value is invariant for all observers.)

An important property of the inner product is that it is invariant (that is, a scalar): a change of coordinates does not result in a change in value of the inner product.

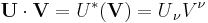

The inner product is often expressed as the effect of the dual vector of one vector on the other:

Here the  s are the components of the dual vector

s are the components of the dual vector  of

of  in the dual basis and called the covariant coordinates of

in the dual basis and called the covariant coordinates of  , while the original

, while the original  components are called the contravariant coordinates. Lower and upper indices indicate always covariant and contravariant coordinates, respectively.

components are called the contravariant coordinates. Lower and upper indices indicate always covariant and contravariant coordinates, respectively.

The relation between the covariant and contravariant coordinates is:

.

.

The four-vectors are arrows on the spacetime diagram or Minkowski diagram. In this article, four-vectors will be referred to simply as vectors.

Four-vectors may be classified as either spacelike, timelike or null. Spacelike, timelike, and null vectors are ones whose inner product with themselves is less than, greater than, and equal to zero respectively (assuming Minkowski metric with signature (+,-,-,-)).

In special relativity (but not general relativity), the derivative of a four-vector with respect to a scalar (invariant) is itself a four-vector.

Examples of four-vectors in dynamics

When considering physical phenomena, differential equations arise naturally; however, when considering space and time derivatives of functions, it is unclear which reference frame these derivatives are taken with respect to. It is agreed that time derivatives are taken with respect to the proper time (τ). As proper time is an invariant, this guarantees that the proper-time-derivative of any four-vector is itself a four-vector. It is then important to find a relation between this proper-time-derivative and another time derivative (using the time of an inertial reference frame). This relation is provided by the time transformation in the Lorentz transformations and is:

where γ is the Lorentz factor. Important four-vectors in relativity theory can now be defined.

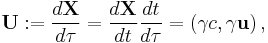

Four-velocity

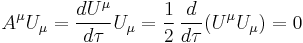

The four-velocity of an  world line is defined by:

world line is defined by:

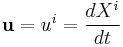

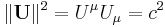

where, using suffix notation,

for i = 1, 2, 3. Notice that

The geometric meaning of 4-velocity is the unit vector tangent to the world line in Minkowski space.

Four-acceleration

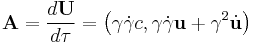

The four-acceleration is given by:

Since the magnitude  of

of  is a constant, the four acceleration is (pseudo-)orthogonal to the four velocity, i.e. the Minkowski inner product of the four-acceleration and the four-velocity is zero:

is a constant, the four acceleration is (pseudo-)orthogonal to the four velocity, i.e. the Minkowski inner product of the four-acceleration and the four-velocity is zero:

which is true for all world lines.

The geometric meaning of 4-acceleration is the curvature vector of the world line in Minkowski space.

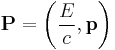

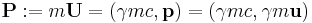

Four-momentum

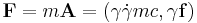

The four-momentum for a massive particle is given by:

where m is the invariant mass of the particle and p is the relativistic momentum.

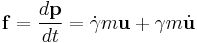

Four-force

The four-force is defined by:

For a particle of constant mass, this is equivalent to

where

.

.

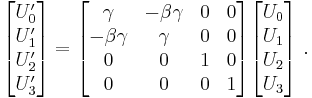

Lorentz transformation

All four-vectors transform in the same manner. In the standard sets of inertial frames as shown by the graph,

Physics of four-vectors

The power and elegance of the four-vector formalism may be demonstrated by seeing that known relations between energy and matter are embedded into it.

E = mc2

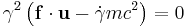

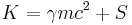

Here, an expression for the total energy of a particle will be derived. The kinetic energy (K) of a particle is defined analogously to the classical definition, namely as

with f as above. Noticing that  and expanding this out we get

and expanding this out we get

Hence

which yields

for some constant S. When the particle is at rest (u = 0), we take its kinetic energy to be zero (K = 0). This gives

Thus, we interpret the total energy E of the particle as composed of its kinetic energy K and its rest energy m c2. Thus, we have

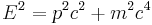

E2 = p2c2 + m2c4

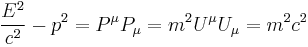

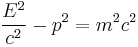

Using the relation  , we can write the four-momentum as

, we can write the four-momentum as

.

.

Taking the inner product of the four-momentum with itself in two different ways, we obtain the relation

i.e.

Hence

This last relation is useful in many areas of physics.

Examples of four-vectors in electromagnetism

Examples of four-vectors in electromagnetism include the four-current defined by

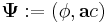

formed from the current density j and charge density ρ, and the electromagnetic four-potential defined by

formed from the vector potential a and the scalar potential  .

.

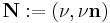

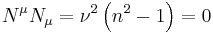

A plane electromagnetic wave can be described by the four-frequency defined as

where  is the frequency of the wave and n is a unit vector in the travel direction of the wave. Notice that

is the frequency of the wave and n is a unit vector in the travel direction of the wave. Notice that

so that the four-frequency is always a null vector.

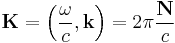

A wave packet of nearly monochromatic light can be characterized by the wave vector, or four-wavevector

The 4-impulse of single photon is

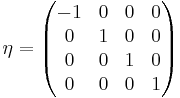

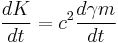

Four-vectors in quantum theory

In relativistic quantum mechanics, the probability density function  is substituted by the time component of a four-vector:[4]

is substituted by the time component of a four-vector:[4]

See also

- four-velocity

- four-acceleration

- four-momentum

- four-force

- four-current

- electromagnetic four-potential

- four-gradient

- four-frequency

- paravector

- wave vector

- Dust (relativity) Number-Flux 4-vector

- Basic introduction to the mathematics of curved spacetime

- Minkowski space

References

- ^ Jean-Bernard Zuber & Claude Itzykson, Quantum Field Theory, pg 5 , ISBN 0-07-032071-3

- ^ Charles W. Misner, Kip S. Thorne & John A. Wheeler,Gravitation, pg 51, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

- ^ George Sterman, An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory, pg 4 , ISBN 0-521-31132-2

- ^ Vladimir G. Ivancevic, Tijana T. Ivancevic (2008) Quantum leap: from Dirac and Feynman, across the universe, to human body and mind. World Scientific Publishing Company, ISBN 978-981-281-927-7, p. 41

- Rindler, W. Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd edn.) (1991) Clarendon Press Oxford ISBN 0-19-853952-5

![\frac{1}{4 \pi i} [\psi \partial_{x_0} \overline{\psi} - \overline{\psi} \partial_{x_0} \psi ]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f3e803898befa1463b5b45910dfb29e4.png)